“In came a fiddler with a music-book, and went up to the lofty desk, and made an orchestra of it, and tuned like fifty stomach-aches.”

“In came a fiddler with a music-book, and went up to the lofty desk, and made an orchestra of it, and tuned like fifty stomach-aches.”

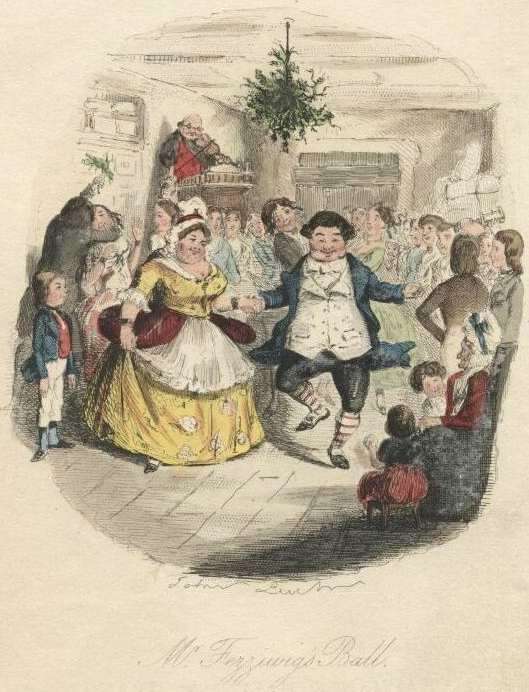

So begins the famous description of Mr. Fezziwig’s Christmas Eve ball in Charles Dickens’ 1843 novel, A Christmas Carol, the full text of which with the original illustrations, including the one shown at left (click to enlarge), may be found at Project Gutenberg.

This is a fun example of, at least, a Victorian writer’s conception of a late 18th century ball which, though given by a successful businessman, is very much of the middle and lower classes rather than of the nobility. Given that Dickens’ family was not wealthy (at one point they ended up in a debtors’ prison), he may have been writing more from personal experience in London in the 1830s than, say, careful research about ballroom practices several decades earlier. So while this is a useful historical document for dance history, which period it is useful for is not entirely clear.

With that in mind, let’s get back to the Fezziwigs. The fiddler mentioned above is the only musician, and the ball is held in a warehouse in which the apprentices (including the young Scrooge) have merely pushed back the furniture to make space to dance:

Every movable was packed off, as if it were dismissed from public life for evermore; the floor was swept and watered, the lamps were trimmed, fuel was heaped upon the fire; and the warehouse was as snug, and warm, and dry, and bright a ball-room, as you would desire to see upon a winter’s night.

The guests the Fezziwigs welcome at their ball include not only their daughters and their own employees but also servants and other local tradespeople and apprentices:

In came the housemaid, with her cousin, the baker. In came the cook, with her brother’s particular friend, the milkman. In came the boy from over the way, who was suspected of not having board enough from his master; trying to hide himself behind the girl from next door but one, who was proved to have had her ears pulled by her mistress.

The country dancing is cheerfully chaotic:

Away they all went, twenty couple at once; hands half round and back again the other way; down the middle and up again; round and round in various stages of affectionate grouping; old top couple always turning up in the wrong place; new top couple starting off again, as soon as they got there; all top couples at last, and not a bottom one to help them! When this result was brought about, old Fezziwig, clapping his hands to stop the dance, cried out, “Well done!” and the fiddler plunged his hot face into a pot of porter, especially provided for that purpose.

The figures Dickens mentions, “hands half round and back again” and “down the middle and up again” are standard country dance figures, and the description of the dance falling apart as couples neglect to wait out at the top of the set and instead plunge right into the dance as an active couple, even without any other couples to dance with, is a hilariously familiar problem to anyone who has taught beginners.

But what is most interesting to me is the very beginning of the description, the “twenty couple at once”. Dickens was writing two decades after the Regency era and its well-documented practice of only the very first couple in the set beginning the dance, which had been standard in country dancing for over a century – probably since its earliest development as a dance form. In America, by the middle of the nineteenth century, musician and dance caller (and prolific producer of dance and music books) Elias Howe would be suggesting in print that all the couples in a set could begin at once, which would eventually become standard practice. But I don’t know exactly when (or even if) that transition took place in England. With “at once” and the “various stages of affectionate grouping”, was Dickens implying a simultaneous start for all the couples, or, since he also mentions a top couple (singular), merely that all twenty couples joined a single set? That would make for a very long dance indeed. A simultaneous start would have been anachronistic for the period of the ball, but perhaps had become typical practice by Dickens’ own young manhood in the 1830s. It’s easy to fall into the trap of projecting the current practice one knows further back in time than is actually valid.

The ball continued with dancing and games and the typical mid-ball pause for supper:

There were more dances, and there were forfeits, and more dances, and there was cake, and there was negus, and there was a great piece of Cold Roast, and there was a great piece of Cold Boiled, and there were mince-pies, and plenty of beer.

And, at last, comes the famous Roger de Coverley:

But the great effect of the evening came after the Roast and Boiled, when the fiddler (an artful dog, mind! The sort of man who knew his business better than you or I could have told it him!) struck up “Sir Roger de Coverley.” Then old Fezziwig stood out to dance with Mrs. Fezziwig. Top couple, too; with a good stiff piece of work cut out for them; three or four and twenty pair of partners; people who were not to be trifled with; people who would dance, and had no notion of walking.

This is not necessarily the literal finishing (final) dance, as Thomas Wilson called it; Dickens does not state specifically that it was the last dance. But it does at least come late in the ball. And the Fezziwigs certainly do have their work cut out for them; twenty couples is an enormous set for this dance. When I conduct balls, I usually keep the sets to six or seven couples, and the dance still takes a good ten minutes. With twenty couples, I could see it going for forty minutes to an hour. The Fezziwigs would only have led it once, one assumes, and not have much to do after the second time through, as the middle-of-the-set couples only participate in the final promenade and cast off (see my description of a Regency-era version of the dance here.) But that is still a long time to stand up in a set!

Dickens also clearly notes the distinction between dancing (doing footwork) and walking.

The Fezziwigs are not intimidated by the length of the set:

But if they had been twice as many—ah, four times—old Fezziwig would have been a match for them, and so would Mrs. Fezziwig. As to her, she was worthy to be his partner in every sense of the term. If that’s not high praise, tell me higher, and I’ll use it. A positive light appeared to issue from Fezziwig’s calves. They shone in every part of the dance like moons. You couldn’t have predicted, at any given time, what would have become of them next.

I always have to laugh at Fezziwig’s calves shining like moons in this passage. Presumably it is a reference to his large calves being shown, hopefully to advantage, in the white stockings commonly worn by men, though the illustration above gives him colorful striped ones.

Dickens actually writes out some of the figures:

And when old Fezziwig and Mrs. Fezziwig had gone all through the dance; advance and retire, both hands to your partner, bow and curtsey, corkscrew, thread-the-needle, and back again to your place; Fezziwig “cut”—cut so deftly, that he appeared to wink with his legs, and came upon his feet again without a stagger.

That isn’t a bad summary of the dance, allowing for the colorful terms. “Advance and retire, both hands to your partner, bow and curtsey” are some of the opening diagonal figures performed with the couple at the very end of the set (again, see my previous description), though not the full list. It’s hard to say whether the lack of the right- and left-hand turns and the dos-á-dos represented an actual change in the dance to a shorter version with fewer diagonal figures by 1843, as certainly did happen just a bit later in the nineteenth century(edited 12/25/13 to add: here is an example of a shorter version), or just a case of Dickens not bothering to write the entire sequence out. Presumably his reading audience would have been generally familiar with the dance.

The “bow and curtsey” as a separate figure are not part of the oldest descriptions (from the early 1800s) that I currently have of the classic “Roger de Coverley” figures, but they are mentioned in descriptions in the mid-nineteenth century and might have already become part of the dance by the early 1840s.

The “corkscrew” and “thread the needle” are fun terms for what I assume is the active couple (the Fezziwigs) weaving their way through the other couples to the bottom of the dance and the final promenade up the set and casting off, which I can imagine as something like threading a needle, or perhaps two needles, one for each line. Later versions of the dance have the top couple making an arch for the other dancers to go through, which would be an even better match for the concept, but it’s unclear to me whether that had been introduced by the early 1840s or not.

And, finally, when the Fezziwigs are either in their places at the bottom of the dance after one iteration or perhaps when they have worked their way back up to the top at the very end of the dance, Fezziwig cuts. I can’t say precisely what showy step that was, but the description hints at a leap in the air, as he has to “come upon” his feet again, or perhaps something akin to the seby-trast step, described by Francis Peacock in Sketches relative to the history and theory, but more especially to the practice of dancing (Aberdeen, 1805) as a series of cuts of the feet. I wouldn’t classify this as part of the dance, just an exuberant personal flourish.

A final indication that this was a middle-class event rather than of the nobility: the early ending. A ball of the nobility might serve supper at midnight and have the attendees dance until dawn. The sensible Fezziwigs keep much earlier hours:

When the clock struck eleven, this domestic ball broke up. Mr. and Mrs. Fezziwig took their stations, one on either side of the door, and shaking hands with every person individually as he or she went out, wished him or her a Merry Christmas. When everybody had retired but the two ’prentices, they did the same to them; and thus the cheerful voices died away, and the lads were left to their beds; which were under a counter in the back-shop.

And on that note, I shall do the same. Merry Christmas to all who celebrate it!

Leave a Reply