In honor of the season…

In his Complete System of English Country Dancing, published circa 1815, Regency-era dancing master Thomas Wilson proclaimed of the dance “Sir Roger De Coverley” that it was

and explained its use as the final dance of the evening (or early morning, given the length of balls of the era):

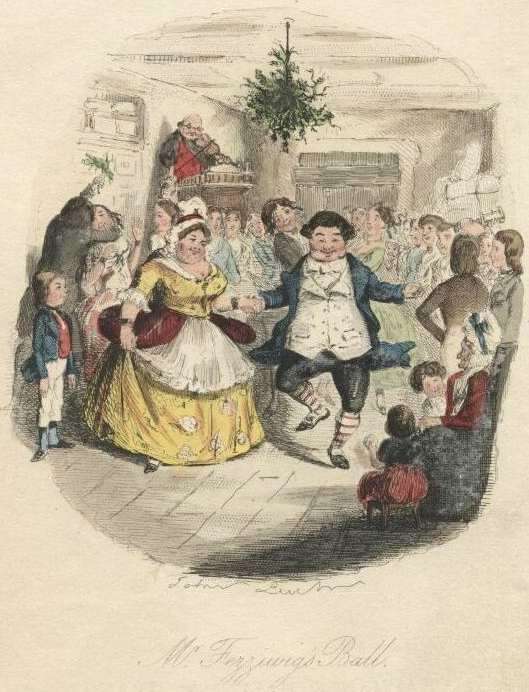

That good humor is most famously in evidence in Charles Dickens’ 1843 novel, A Christmas Carol, in which the dance is done during at Mr. Fezziwig’s ball during the flashback to Christmas Past and Scrooge’s apprenticeship. The era of the flashback is unclear; the original illustration (at left; click to enlarge) seems to depict the late 18th century, judging from the clothing, though that would make Scrooge quite elderly by 1843. The text also offers Marley, who has been dead a mere seven years, in a pigtail and skirted coat; again, fashions of the late 18th century. It is also possible that both Fezziwig and Marley were simply old-fashioned in their dress or, in Marley’s case, too cheap to buy new clothing. One suspects Dickens was not overly concerned with such details! But having been born in 1812, Dickens would have grown up with a “Sir Roger De Coverley” much like the one described below.

That good humor is most famously in evidence in Charles Dickens’ 1843 novel, A Christmas Carol, in which the dance is done during at Mr. Fezziwig’s ball during the flashback to Christmas Past and Scrooge’s apprenticeship. The era of the flashback is unclear; the original illustration (at left; click to enlarge) seems to depict the late 18th century, judging from the clothing, though that would make Scrooge quite elderly by 1843. The text also offers Marley, who has been dead a mere seven years, in a pigtail and skirted coat; again, fashions of the late 18th century. It is also possible that both Fezziwig and Marley were simply old-fashioned in their dress or, in Marley’s case, too cheap to buy new clothing. One suspects Dickens was not overly concerned with such details! But having been born in 1812, Dickens would have grown up with a “Sir Roger De Coverley” much like the one described below.

The tune for the dance is in slip jig (9/8) time. Here is a brief snippet of the tune, taken from the Spare Parts album The Regency Ballroom:

While there are other recordings of the tune available, I recommend this one for Regency-era dancing, as it offers a lengthy enough track to do the entire dance with five or six couples and reasonably period instrumentation of flute, violin, and piano. Three other 9/8 tunes of the period are added to make a medley, returning to the original tune at the end.

The dancers form a column of couples, facing partners, ladies on one side and gentlemen on the other. The top of the set (nearest the music) should be to the gentlemen’s left and the ladies’ right. The initial part of the dance is performed in turn by the top lady and bottom gentleman, followed by the top gentleman and bottom lady. For convenience, I will refer to these pairs as the first and second diagonals, though those terms are not period. The second part is led by the top (active) couple, though the other couples join in as well partway through.

Part one

- The first diagonal pair goes forward and meets in mid-set, then retreats to places. The second diagonal does the same.

- The first diagonal then turns by their right hands; the second diagonal the same.

- The first diagonal turns by the left hands; second the same.

- The first diagonal turns by both hands (clockwise); second the same.

- The first diagonal meets and performs a dos-à-dos; second the same.

Part two

- The top (active) couple cross over (passing by right shoulders), move one place down the outside of the set, cross over again (between the second and third couples), and repeat all the way to the bottom of the set, crossing over one final time at the very bottom if necessary to get back to their own sides. Wilson notes helpfully that if the set is very long, they may move down two places on each cross to speed things up.

- The active couple (currently at the bottom) now takes promenade position (right hand in right crossed over left in left) and promenades up the center of the set. The other couples follow, falling in from the bottom. At the top of the set, the active couple casts off, followed by the other couples, now in reverse order. The active couple reaches the bottom and stays there; all the other couples have now moved up one place.

- The dance restarts from the beginning with new people in the role of the first and second diagonals, and is continued until every couple has had a chance to dance the active role.

Wilson, writing in an earlier (1808) manual, An analysis of country dancing, is specific that

…this holds good for any number of persons. If there are twenty couple [sic], these figures are performed by the couples at the top and bottom of the room.

For modern dancers with a shorter attention span, dividing into sets of five or six couples is more practical. In the case of sets dancing at different rates, the dance should be continued until the slowest set has finished.

Reconstruction issues

The dance instructions are straightforward in all elements but one: Wilson uses the term allemande to describe the final figure performed by the two diagonal pairs. While the several possible meanings of allemande during this era are too complicated to go into in this post, it appears to me that Wilson in his writings uses the term to mean a simple dos-à-dos, as shown in his illustration here, described as moving “round each other’s situation back to back.” Later versions of the dance and its descendant, the Virginia Reel, specify the dos-à-dos.

In his 1816 compendium of music and dance figures, A Companion to the Ball Room, Wilson specifies that

In crossing, the Lady passes in front of the Gentleman, that is, always passing the Gentleman on her Right Hand.

Steps for Sir Roger de Coverley

It is unclear what sort of steps would have been done in the early 19th century to music written in 9/8 time. In A Companion to the Ball Room, Wilson states clearly that

Tunes in 9/8 always require Irish Steps, whatever may be their origin

but unfortunately neglects to explain what said steps are. A simple skipping step (step-hop) works, but given that the dance is generally performed at the very end of the evening, fatigued dancers will tend to devolve to simply walking through the figures.

One critical element, often ignored, is that the music is in compound triple (9/8) time and thus breaks down in threes rather than twos. This means that figures should be performed with six or twelve steps, e.g. six steps forward and six steps back for each diagonal to advance and retire. While in the second part of the dance the figures will take an amount of music proportional to the length of the set and therefore unpredictable, starting each figure of the first part with the phrase of the music and using six or twelve steps to complete it will make the dance more musically graceful. With multiple sets, a caller can be of little help in this, since during part two the sets will tend to become skewed from each other, and after the first repetition the dancers will effectively be on their own.

Sir Roger de Coverley through time and space

A dance to the distinctive “Roger de Coverley” tune first appeared in the ninth edition of The Dancing Master, dated 1695, under the title “Roger of Coverly.” The dance is a standard longways progressive one, however, with no relationship to the finishing dance of a century later.

During the late 18th and early 19th century, tunes and dance figures were not tightly linked together as they are in modern English Country Dancing. It was quite common to set different figures to a popular tune or to use the same set of figures with many different tunes. In keeping with this custom, even the tune “Sir Roger de Coverley” was recycled for use with the normal style of country dance by the ever-present Thomas Wilson, who offered a normal longways progressive figure for the tune on page 107 of his 1816 collection of dance figures for popular tunes, The treasures of Terpsichore. A footnote declares that this is the same tune used for the finishing dance and refers the reader to one of Wilson’s other manuals for the figures.

Finally, the dance crossed the ocean sometime in the early 19th century, became detached from the original tune, and took up residence in America in slightly different form as the Virginia Reel. Dance manuals from later in the nineteenth and even early twentieth centuries offered variant versions of the dance under one title or the other; at some point I will survey some of these later variations. (Edited to add: and I finally did one of them, here, and another one, here!)

A very merry Christmas to all who celebrate it!

Leave a Reply