Long, long, ago I published a reconstruction of the mid-19th century American contra (country) dance published as “Harvest Home” in some of Elias Howe’s dance compilations. I have nothing new to add to that reconstruction, but as I’ve collated more and more contra dances of that era, I’ve found the same figures under a couple of other names in other source, including one predating Howe’s publication of it, with a suggestive pattern of differences.

(more…)Category: Country Dance

-

Another Regency “Sir Roger de Coverley”

It’s always interesting to find a roughly contemporary version of a classic dance that is recognizably the same dance…but not quite the same.

I generally use Thomas Wilson’s version of “Sir Roger de Coverley” as my default version for the Regency era, mostly because it was the first one I encountered. But it was not the only version of the standard figures in the Regency era, even leaving aside the standard country dances and the other whole-set dances (such as the very odd one I described here) set to the same tune. The version published in Platts’s popular & original dances for the pianoforte, violin &c., with proper figures. Vol. 3, no. 25 (London, 1811) is almost precisely contemporary with the version Wilson was publishing from at least 1808 (in An Analysis of Country Dancing) onward. The description has three notable differences, one of which makes me want to seriously reconsider how I teach and perform the dance. I’ve transcribed the description at the bottom of this post for those who want to see for themselves.

-

Regency Oddities: Roger de Coverley

Wrapping up my little series on extended-Regency-era oddities, let’s talk about an unusual version of the English finishing dance, Sir Roger de Coverley! This is one of the rare dances where tune and dance are so tightly associated that it’s reasonable to give the dance the tune name.

I discussed a typical Regency-era version of the classic Sir Roger de Coverley figure long, long ago. Since then, I’ve accumulated a number of other versions of the figure with the same characteristic elements: opening figures performed on the long diagonals followed by whole-set figures that end with the original top couple progressed to the bottom. I’ve written up a couple of later nineteenth century versions here and here.

Now, this is not to say that there were never any other, more typical, country dance figures set to the “Roger de Coverley” tune. In its earliest appearance with dance figures in the ninth edition of Playford’s The Dancing Master, published in 1695, it is printed with a normal progressive figure, completely unrelated to the later dance. One hundred and thirty years after that, a different figure, very generic-Regency, was published with it in Analysis of the London Ball-Room (printed for Thomas Tegg, London, 1825). Never underestimate the willingness of music publishers and dancers, to recycle a tune.

But there’s one set of figures I’ve found printed with “Sir Roger de Coverley” which is a real oddity:

-

A shorter Victorian “Sir Roger de Coverley”

Over the twelve years I’ve been writing Kickery, I’ve twice discussed versions of Sir Roger de Coverley, the English “finishing dance” that was the direct ancestor of America’s Virginia Reel: a Regency-era version from Thomas Wilson and a Victorian-era version probably originated by Mrs. Nicholas Henderson. The latter version of the dance, which shortened the figures and added an introductory figure for all the dancers, appeared in several English sources from around 1850 to 1870. But it was not the only version in mid-nineteenth century England; at least two variations of a full version more like the Regency one continued to appear in dance manuals, and a fourth version, shortened even further, turned up occasionally as well.

The dance being strongly associated with Christmas due to its appearance at Mr. Fezziwig’s ball in Charles Dickens’ 1843 novel, A Christmas Carol, Christmas Eve seems an appropriate time to discuss this extremely short version.

(more…) -

Aurora Waltz / Hungarian Waltz – Contra Dance

It’s been quite some time since I’ve added a nineteenth-century American contra dance to Kickery. Here’s a waltz contra from the ever-useful Elias Howe that, with only a few bars of turning waltz, is an easy dance for beginners. The set of figures appears in near-identical form in at least four of Howe’s numerous dance manuals: the Complete ball-room handbook (1858), The pocket ball-room prompter (1858), and the American dancing master, and ball-room prompter (1862 and 1866).

The original text:

First couple balance, cross over and go down outside below two couples — first couple balance again and waltz up to place — down the centre, back and cast off — swing six

-

Fessenden’s “The Rustick Revel”, 1806

Reading onward in Thomas Fessenden’s Original Poems (1806), what should turn up but another poem about dance, even lengthier and more detailed than “Horace Surpassed”! “The Rustick Revel” is less impressive as a poem, being made up entirely of rhyming couplets of utterly regular rhythm, but it’s even thicker with dance references. As Nathaniel Hawthorne said in his biographical sketch of Fessenden:

He had caught the rare art of sketching familiar manners, and of throwing into verse the very spirit of society as it existed around him; and he had imbued each line with a peculiar yet perfectly natural and homely humor.

Hawthorne was referring to a different poem, but it could easily serve for this one as well. Among the highlights are the very calculated invitation list, the squire calling a dance, people messing up the figures, and trying to get out of paying the bill.

Once again, I’ll give the entire poem in bold with my own commentary interspersed in italics. Fessenden’s own footnotes have been moved to the end.

-

Fessenden on New England country dancing, 1806

“Horace Surpassed” (lengthily subtitled “or, a beautiful description of a New England Country-Dance”) was published by the American author Thomas Green Fessenden (left) in his 1806 collection, Original Poems. Fessenden (1771-1837) was, according to the biographical notes here, a lawyer, poet, farmer, journalist, newspaper editor, and member of the Massachusetts legislature. He was born in Massachusetts, educated at Dartmouth, and spent most of his life in New England. His original fame as a poet grew from the 1803 work “Terrible Tractoration”, a satire about physicians who refused to adopt a quack medical device. (Yes, really!)

“Horace Surpassed” (lengthily subtitled “or, a beautiful description of a New England Country-Dance”) was published by the American author Thomas Green Fessenden (left) in his 1806 collection, Original Poems. Fessenden (1771-1837) was, according to the biographical notes here, a lawyer, poet, farmer, journalist, newspaper editor, and member of the Massachusetts legislature. He was born in Massachusetts, educated at Dartmouth, and spent most of his life in New England. His original fame as a poet grew from the 1803 work “Terrible Tractoration”, a satire about physicians who refused to adopt a quack medical device. (Yes, really!)In his spare time, Fessenden evidently liked country (contra) dancing, and his poem is a cheerful look at the characters of rural New England society: agile Willy Wagnimble, clumsy Charles Clumfoot, graceful Angelina, etc. The “New England Country-Dance” in the subtitle should be understood as referring to a social evening, not to an actual country-dance.

A rather catty review quoted the poem at length

not because it is superiour to the rest, but as a fair specimen of the work, and it describes an amusement which is “all the rage.”

— The Monthly anthology, and Boston review. (July, 1806)Fessenden topped his poem with a quote from Horace’s Odes. “Iam satis terris nivis atque dirae” (“Enough of snow and hail at last”) is the opening line of “To Augustus, The Deliverer and Hope of the State” (1.2). This particular Ode concerns the disastrous overflowing of the Tiber, possibly as a punishment of the gods for the ill deeds of Rome (notably, the assassination of Julius Caesar), with Augustus as its hoped-for saviour. An 1882 translation of the Ode may be found here. I must confess that I cannot detect any thematic connection between it and Fessenden’s poem, so I’ll chalk it up to Fessenden’s ego and desire to be recognized as a poet.

The full original text with my best approximation of the formatting is in bold below, with a few comments of my own interspersed in italics. In the absence of page breaks, the footnotes have been moved to the end.

-

Green Mountain Volunteers

Green Mountain Volunteers is currently fourth on my list of go-to contra dances for the 1910s, after the Circle; Hull’s Victory; and Lady of the Lake. It really ought to be sixth, after Boston Fancy and Portland Fancy as well, but the former is too much like Lady of the Lake, and the latter I’m still thinking about.

Unlike the five dances listed above, which appear on a pair of Maine dance cards from 1918-1919, I do not have dance card evidence for this one. The only pre-1937 source for it, in fact, is Elizabeth Burchenal’s American Country-Dances, Volume I (New York & Boston, 1918), in which she lists it among the dances “half-forgotten or less used” by the late 1910s:

Some of the most widely used of the contra-dances to-day in New England are The Circle, Lady of the Lake, Boston Fancy, Portland Fancy, Hull’s Victory, Soldier’s Joy, and Old Zip Coon (or, the Morning Star); while among the half-forgotten or less used ones are Chorus Jig, Green Mountain Volunteers, and Fisher’s Hornpipe.

-

Reminiscences, 1865

I have what seems like an endless collection of works of nineteenth-century women’s fiction that I plow through for the dance references whenever I have the chance. Most of them are overly sentimental and laden with heavy-handed moral messages. “Reminiscences”, which was serialized in the American women’s periodical Godey’s Lady’s Book from February to June, 1865, was no exception to this, alas, but at least it was relatively short.

The background of the piece is a bit of a mystery. The author is the same “Ethelstone” credited with “Dancing the Schottische” (Godey’s, July 1862), which I discussed a few years ago. I’ve never been able to locate any information about this author. And “Reminiscences” adds a new element of confusion because it is written in first person and purports to be the story of one Ethel Stone. Was “Ethelstone” actually a woman named Ethel Stone? Is this fiction masquerading as memoir? Or part of an actual memoir of a life that oh-so-conveniently included the elements of a mid-nineteenth-century morality tale? That seems unlikely, so I assume that it’s fiction. But I may never know for certain.

-

Flower Girl’s Dance

Flower Girl’s Dance is an American Civil War-era contra dance that I remember dancing way back in the early 1990s when I first started doing mid-nineteenth-century dance. But the version we did does not actually match that found in any source I’ve ever seen. And it’s easy to see why: the versions given in the sources don’t actually work very well. And now that I’ve reconstructed the California Reel, I have a little theory about why that is.

The earliest sources I have for Flower Girl’s Dance are Elias Howe’s two 1858 books, the Pocket Ball-Room Prompter and the Complete Ball-Room Handbook. I strongly suspect that all the later sources were copying to some degree from Howe. So let’s look at Howe’s instructions:

FLOWER GIRL’S DANCE.

(Music: Girl I left behind me.)

Form as for Spanish Dance. All chassa to the right, half balance–chassa back, swing four half round–swing four half round and back–half promenade, half right and left–forward and back all, forward and pass to next couple (as in the Haymakers).There are some minor differences of spelling and punctuation, but the wording is essentially the same across almost forty years of Howe publications. Taken at face value with the hash marks setting off eight-bar musical strains, this yields a 40-bar dance:

-

California Reel

There’s the famous Virginia Reel. There’s a Kentucky Reel. Why not a California Reel?

Unlike those other two reels, which are full-set dances, the California Reel is a normal progressive contra dance in the “Spanish Dance” format: couple facing couple, either down a longways set or in a circle. For this particular dance, a line of couples will work better.

I have five sources for California Reel, though two of them are simply later editions of other sources:

- The ball-room manual, containing a complete description of contra dances, with remarks on cotillions, quadrilles, and Spanish dance, revised edition, presumed to be by William Henry Quimby (Belfast, Maine, 1856; introduction signed W. H. Q)

- The ball room guide : a description of the most popular contra dances of the day, (Laconia, New Hampshire, 1858)

- The ball-room manual of contra dances and social cotillons, with remarks on quadrilles and Spanish dance, vest pocket edition, presumed to be by William Henry Quimby (Belfast, Maine, and Boston, 1863) (later edition of first source above, again signed W. H. Q.)

- Howe’s New American Dancing Master by Elias Howe (Boston, 1882)

- Howe’s New American Dancing Master by Elias Howe (Boston, 1892)

All of them have the same language in the description, varying only in punctuation and spelling. I am reasonably sure that the text in most of these sources was copied from either the 1856 source or some earlier source.

-

Mr. Layland’s Polka Contre Danse

There are at least five different dances in the second half of the nineteenth century whose name is some variation on the generic “polka country dance”. The one I’m looking at here was published as both “Polka Contre Danse” and just “Polka Contre”. Unusually, it is attributed to a particular dancing master, Mr. Layland, who was active in London in the mid-19th century. I’ve mentioned him before in the context of his mescolanzes. That makes it very much an English dance, despite its appearance in a couple of American dance manuals.

My first English source for the Polka Contre Danse, The Victoria Danse du Monde and Quadrille Preceptor, dates to the early 1870s, but I suspect that it actually dates back to the 1850s. It actually appears earlier in two of the manuals of Boston musician/dance caller/publisher Elias Howe, the earlier of which is from 1862. Howe was a collector and tended to throw dances from every book he collected into his own works, so I suspect there is an earlier English source somewhere, possibly by Layland himself. Maybe someday I’ll find it.

Until then, on with Polka Contre Danse!

-

Waltzing Around

A recent mailing list discussion centered on how to quickly teach people to do a "waltz-around", the style of country dance progression in which two couples waltz around each other once and a half times. This is most famously part of the mid- to late-nineteenth-century Spanish Dance, as well as other American waltz contra dances (such as the German Waltz and Bohemian Waltz). It dates back at least as far as the late 1810s to early 1820s in England, when Spanish dances were an entire genre of country dances in waltz time, and both they and ordinary waltz country dances featured this figure, sometimes under the names "poussette" or "waltze". I expect it goes even further back on the European continent, but I haven't yet pursued that line of research.

As a dancer, the waltz-around has always been one of those figures that I just…do. I'd observed that it's difficult for beginners to master the tight curvature of the circle and making one and a half circles in only eight measures, but as an experienced waltzer, I've long been able to do it instinctively. And I'd never broken down precisely what I did or worked out how to explain it to others.

So I suppose it's about time!

-

A miscellany of mescolanzes

I don’t often get asked to write about particular topics on Kickery, but I recently received, via the comments here, a request from a teacher at Mrs. Bennet’s Ballroom, a historical dance group in London, UK, for a few of my favorite figures for mescolanzes, the four-facing-four country dance format I surveyed earlier this year. Since the focus of the group seems to be the Regency era, I’ll stick with figures from manuals by London dancing master G. M. S. Chivers, which are from the very tail end of the official Regency period (1811-1820) and a few years after.

As I discussed in my earlier survey, Chivers seems to have really liked the mescolanze format, and a few other dancing masters and authors picked it up, but other than the special case of La Tempête, I can’t really say with confidence that mescolanzes were a popular or even common dance form in nineteenth-century England. But the format appears across enough different sources that I’m comfortable with using it sparingly to add variety for the late Regency and immediate post-Regency era. I don’t ever do more than one mescolanze at a ball, however.

-

On Old Fashioned Dances, 1926

On January 21, 1926, a column unfavorably comparing modern dancing to that of earlier eras was published in the Lewiston Evening Journal, published in Lewiston, Maine. “On ‘Old-Fashioned Dances’ ” appeared under the column title “Just Talks On Common Themes” and the byline of A. G. S. The initials are those of Arthur Gray Staples (1861-1940), a Maine writer who was the editor-in-chief of the Lewiston Evening Journal (later just the Lewiston Journal) from 1919-1940. “Just Talks On Common Themes” was his daily column. Staples described these columns many years later in an inscription of one of his books to the Maine State Library:

The only claim for these things is their spontaneity. They write themselves — “after hours,” chiefly. In their day and generation many good folk seemed to like some of them and many did not.

A collection of the columns was published in 1919 or 1920 and may now be found online at archive.org. Later collections were issued in 1921 and 1924, but a 1926 column was obviously not included in any of them. Fortunately, it is now online in its original newspaper publication.

-

Tracking the Mescolanzes

The topic of mescolanzes, four-facing-four country dances, and whether the famous dance La Tempête was the only surviving member of the genre by the mid- to late nineteenth century, came up in an email exchange recently. Mescolanzes are one of those dance genres for which I have spent years slowly accumulating examples, so I thought I’d talk a little bit about the format and where dances called mescolanzes appeared over the course of the nineteenth century.

I’m going to limit this quick survey to more-or-less anglophone countries — England, America, Scotland, Canada, and Australia — since I’ve not yet collated all the information I have from other countries. I’m also not going to discuss La Tempête specifically, since that is an enormous topic all on its own. Here and now, I will only survey dances appearing under the name or classification “mescolanze” and its several (mis)spellings.

-

Teaching the hey for three

I didn’t realize my way of teaching heys for three was particularly unusual until one of my regular musicians, who is himself a contra dance caller, commented on it, impressed by how quickly I was able to get a roomful of dancers at a public ball (meaning dancers of wildly mixed ability and experience) doing heys in unison. Since heys of one sort or another are especially popular in early nineteenth century dance, I teach them frequently and prefer not to take too much time about it, especially when calling at a ball.

My little trick for teaching a hey for three is to start by teaching it from an L-shaped formation, as a “corner hey”, rather than in a straight line. I find that it can be difficult for dancers, especially beginners, to visualize the figure-eight path of the hey when they all start in a straight line, and that it is not intuitively obvious in which direction the second and third dancers move when everyone starts at once (as they should!) rather than one dancer moving and the other two waiting out a measure or two before starting.

Doing a corner hey simplifies things.

-

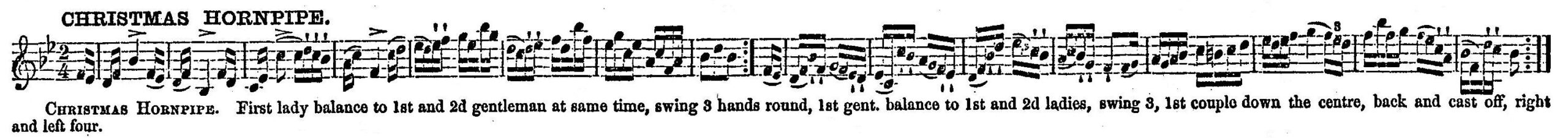

Christmas Hornpipe

After my last experience with hornpipes, it’s nice to have a contra recommended for tunes called hornpipes without having to hunt down or worry unduly about the music!

“Christmas Hornpipe” is the name of the tune in the image below, taken from Elias Howe’s Improved Edition of the Musician’s Omnibus (Boston, 1861). Click to enlarge.

Whether to call the figures “Christmas Hornpipe” is a more ambiguous question, since they appear with other tunes as well (more on this below), reused in the same way figures were in the extended Regency era, from at least 1858 through the mid-1890s.

-

Same-Gender Couples in the Regency Ballroom

One of the critical elements of serious dance history is cross-checking what the dancing masters says in dance manuals against the evidence we have — if any — of what people actually did. Those two things aren’t always the same. Dancing masters generally explain what people ought to be doing, sometimes interspersed with lengthy complaints about what people are doing instead. Both rules and complaints are useful guides, depending on whether one wants to strive to dance well and politely by period standards, or dance badly and rudely, as no doubt happened plenty in practice.

But the very best evidence comes from the letters and diaries of people who actually lived in the relevant era. Here’s a great example of how a letter supports something that dancing masters wrote about in the Regency era: people of the same gender dancing together.

-

The Trio

Since I frequently have to deal with an imbalance in numbers between the ladies and the gentlemen at nineteenth century balls, I’m always interested in dances that use a trio formation. This can be one gentleman with two ladies or vice-versa, though the former is the more common situation.

This dance, simply called “The Trio”, appears in at least two editions of Elias Howe’s American dancing master, and ball-room prompter (Boston, 1862 and 1866). Howe’s instructions are a bit vague and neglect to mention the actual timing of the figures, but a little experimentation convinced me that the following reconstruction is workable and fun. This is an extremely easy dance, good for groups of beginners.

-

Trips to Paris

This post is for Allison, Graham, and Alan, who know and care.

If I expect to get anything done in my life, I cannot spend my time wandering around the net getting irritated by the dance history errors. But I do pay attention when they arrive by email. So I noticed when a mailing list query about how best to dance “A Trip to Paris” at a Jane Austen ball appeared in my inbox. Happily, I was neither the first nor the last list member to jump in with some version of “That dance is from Walsh, from 1711, and does not belong at a Jane Austen ball!” (Jane Austen lived from 1775-1817, and her dancing days would have started in the early 1790s.)

I did get intrigued by one comment in the ensuing discussion: that the dance had been “republished by Thomas Cahusac in 24 Country Dances for 1794” and therefore might have been danced by Jane Austen. That’s a terrifically specific citation — hurray! — but I instantly doubted it, since (1) very few dances or tunes of the earlier style were reprinted that late (young people, then and now, not being particularly into dancing their great-grandparents’ dances), and (2) I already knew there were other tunes called “A Trip to Paris” and other dance figures printed with them. As another list member pointed out, it’s a very generic sort of title.

-

A ballroom brawl, 1804

Going beyond simple rudeness in the ballroom, here’s a wonderful account of a French-American culture clash turned violent at a ball in New Orleans on January 23, 1804. Aside from showing what people of that era would fight over and how hair-trigger tempers were in New Orleans in particular at that time, it also usefully documents some ballroom dance practices of the era. Slowly piecing together such tidbits eventually allows me to draw larger conclusions.

I’m not going to explain the whole background of the Louisiana Purchase, which transferred an enormous swathe of North America from French to American control in 1803, but it is worth noting that the formal transfer of New Orleans itself took place on December 20, 1803, only a month or so before the incident described. There is a suggestion earlier in the article that feelings were running high among the French in the wake of (perceived?) American disrespect during the replacement of the French flag with the American one. There had already been a “slight misunderstanding” at a previous assembly on January 6th. The fight on the 23rd is a small example of the sort of cultural conflicts that would be a problem in New Orleans society for decades afterward.

-

Tired of the company, 1789

I’ve recently been reminded by some discussions on a mailing list that there are plenty of people who don’t really have much grasp of the social context of dance in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century or that a ball could be a much more complicated and socially perilous event than just a bunch of folks getting together and having a nice time dancing.

Here’s an interesting example of rudeness on the dance floor wielded as a social weapon.

-

“agoing to dance the spanish dance”

“…George Cowls says tell Nancy he is right in his glory to day and when he comes home he is agoing to dance the spanish dance with you and he says tell Abby he is agoing through ceders swamp with her…”

— Pvt. Jairus Hammond to Nancy Titus, December 8, 1862Here’s rare documentation of a specific dance: a mention in a letter from a Union soldier during the American Civil War to his sister, dated one hundred and fifty-two years ago today, that another man plans to dance the Spanish Dance (previously described here) with her when he returns. There has been no real doubt that the Spanish Dance was actually danced and was as popular as its frequent appearance in dance manuals suggests. I have found it listed on dozens of dance cards. But this is another little piece of documentation demonstrating that its popularity extended well down the social scale.

-

CD Review: Dance and Danceability

Getting useable music for Regency-era dancing is a chronically frustrating problem, and there are very few albums I can recommend wholeheartedly. Many of the recordings advertised as “Regency” or “Jane Austen” suffer from a weirdly expansive idea of “Regency era” that goes back to the 17th century or forward to the 20th. Almost all have an incorrect number of repeats of the music for period dancing, which matches repeats to set length in a specific way that does not accord with modern recording habits.

Dance and Danceability is an Austen-themed album of country dance tunes from the Scottish dance band The Assembly Players (Nicolas Broadbridge, Aidan Broadbridge, and Brian Prentice). Aidan Broadbridge is a name that may be especially recognizable to Austen enthusiasts — he was the fiddler for the 2005 film adaptation of Pride & Prejudice

(paid link) as well as the fictionalized pseudo-biopic Becoming Jane

(2007) (paid link).

Sadly, this is one of the frustrating CDs.