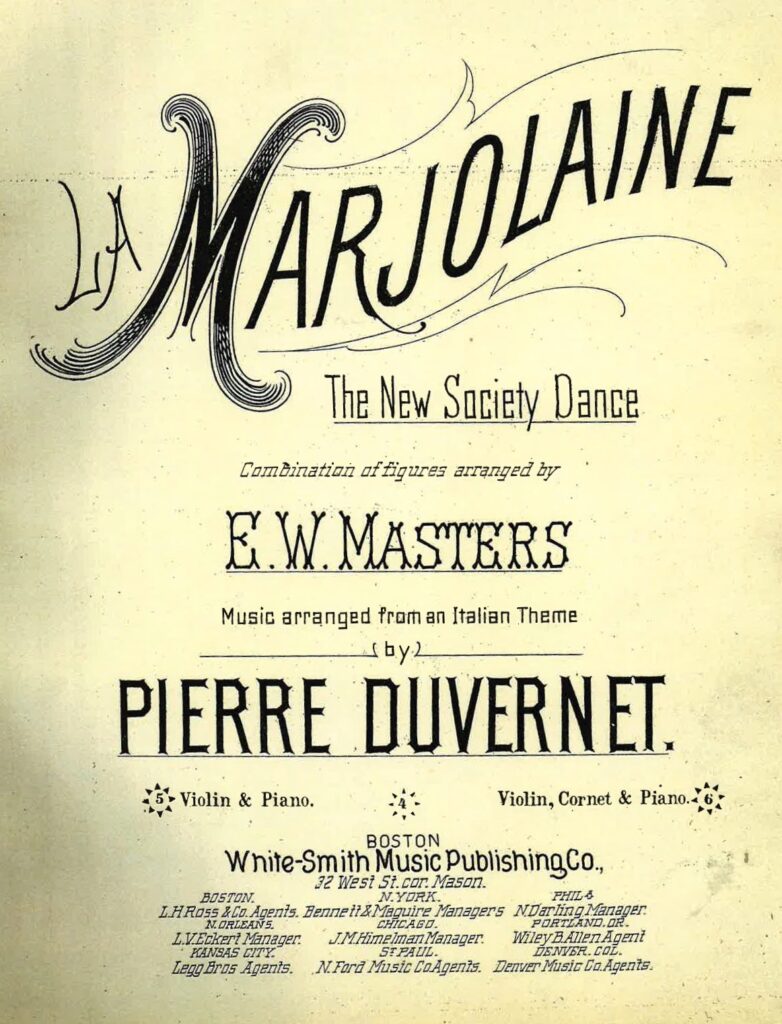

La Marjolaine, The New Society Dance, was published by the White-Smith Music Publishing Co. in 1888. The music was “arranged from an Italian theme” by Pierre Duvernet with an accompanying “combination of figures” by E. W, Masters. The title page of the sheet music may be seen below; click to enlarge.

The figures are a very simple eight-bar sequence: a typical late nineteenth century variant of the “heel and toe” polka combined with the four-slide galop. Although the dance is clearly a two-step, complete with music in 6/8, that term is never used in the instructions – an interesting hint that the two-step was not yet well-known as a term in 1888 as it would become in the 1890s.

(more…)