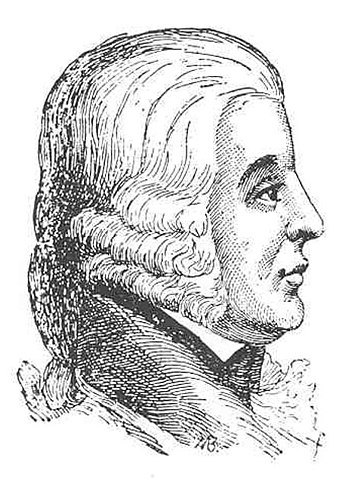

“Horace Surpassed” (lengthily subtitled “or, a beautiful description of a New England Country-Dance”) was published by the American author Thomas Green Fessenden (left) in his 1806 collection, Original Poems. Fessenden (1771-1837) was, according to the biographical notes here, a lawyer, poet, farmer, journalist, newspaper editor, and member of the Massachusetts legislature. He was born in Massachusetts, educated at Dartmouth, and spent most of his life in New England. His original fame as a poet grew from the 1803 work “Terrible Tractoration”, a satire about physicians who refused to adopt a quack medical device. (Yes, really!)

“Horace Surpassed” (lengthily subtitled “or, a beautiful description of a New England Country-Dance”) was published by the American author Thomas Green Fessenden (left) in his 1806 collection, Original Poems. Fessenden (1771-1837) was, according to the biographical notes here, a lawyer, poet, farmer, journalist, newspaper editor, and member of the Massachusetts legislature. He was born in Massachusetts, educated at Dartmouth, and spent most of his life in New England. His original fame as a poet grew from the 1803 work “Terrible Tractoration”, a satire about physicians who refused to adopt a quack medical device. (Yes, really!)

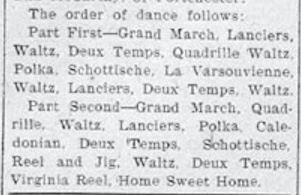

In his spare time, Fessenden evidently liked country (contra) dancing, and his poem is a cheerful look at the characters of rural New England society: agile Willy Wagnimble, clumsy Charles Clumfoot, graceful Angelina, etc. The “New England Country-Dance” in the subtitle should be understood as referring to a social evening, not to an actual country-dance.

A rather catty review quoted the poem at length

not because it is superiour to the rest, but as a fair specimen of the work, and it describes an amusement which is “all the rage.”

— The Monthly anthology, and Boston review. (July, 1806)

Fessenden topped his poem with a quote from Horace’s Odes. “Iam satis terris nivis atque dirae” (“Enough of snow and hail at last”) is the opening line of “To Augustus, The Deliverer and Hope of the State” (1.2). This particular Ode concerns the disastrous overflowing of the Tiber, possibly as a punishment of the gods for the ill deeds of Rome (notably, the assassination of Julius Caesar), with Augustus as its hoped-for saviour. An 1882 translation of the Ode may be found here. I must confess that I cannot detect any thematic connection between it and Fessenden’s poem, so I’ll chalk it up to Fessenden’s ego and desire to be recognized as a poet.

The full original text with my best approximation of the formatting is in bold below, with a few comments of my own interspersed in italics. In the absence of page breaks, the footnotes have been moved to the end.

(more…)