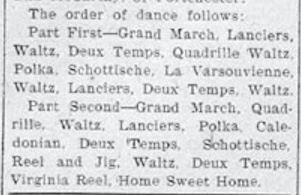

On March 18, 1876, the Morning Herald of Wilmington, Delaware, published a short blurb covering a recent “masquerade party” given by one Professor Webster at the Dancing Academy Hall. Unusually, the newspaper coverage says nothing about the costumes other than that there were enough of them to “have exhausted a first class costumer’s establishment, and have taxed the ingenuity of an artist.” Instead, we get an actual dance program, consisting entirely of quadrilles, Lanciers, and glide waltzes, and accompanied by names which might be masquerade costumes, though I’m not certain of that.

Professor Webster was a long-time Wilmington dancing master – he was still teaching as late as June 4, 1899, when the Sunday Morning Star reported on the closing reception of his current series of dance classes (see about two-thirds of the way down the first column here.)

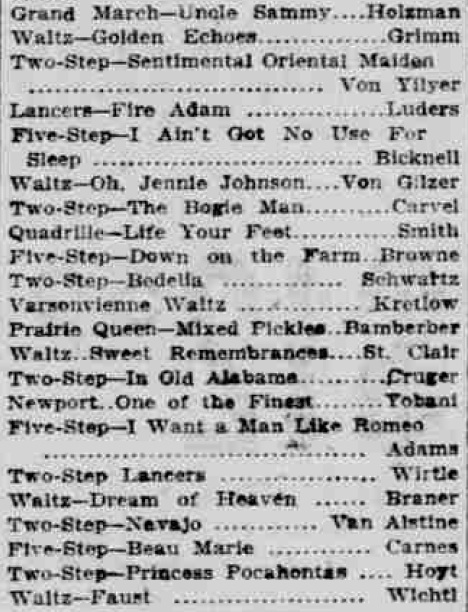

Here’s the list of dances, in order.