I come across little tidbits of information about dance history in the oddest places.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, better known as the Mormon church, places a premium on genealogical research for theological reasons. This has inspired one Mormon family, the Blakes, to create a website about their immediate ancestors.

Among the reminiscences on their site is an interesting excerpt from the book In Search of Zion: King, Youngberg and Allied Families by Richard K. Hart, which apparently features the recollections of one James King, a friend of Blake ancestor Walter Frank Blake (1880-1965).

According to the information on the Blake family site, Walter Blake was born in England and immigrated to Utah with his parents at the age of two. His mother converted to the Mormon faith in the 1880s and Walter and his siblings followed suit. The King family, already Mormons, were neighbors and friends. James King recounted his memories of life in turn-of-the-century Utah farm country to his wife in 1959. Though the stereotype of Mormons is rather stuffy, apparently social dancing was (and is) allowed and even encouraged, provided that it doesn’t get too intimate or suggestive.

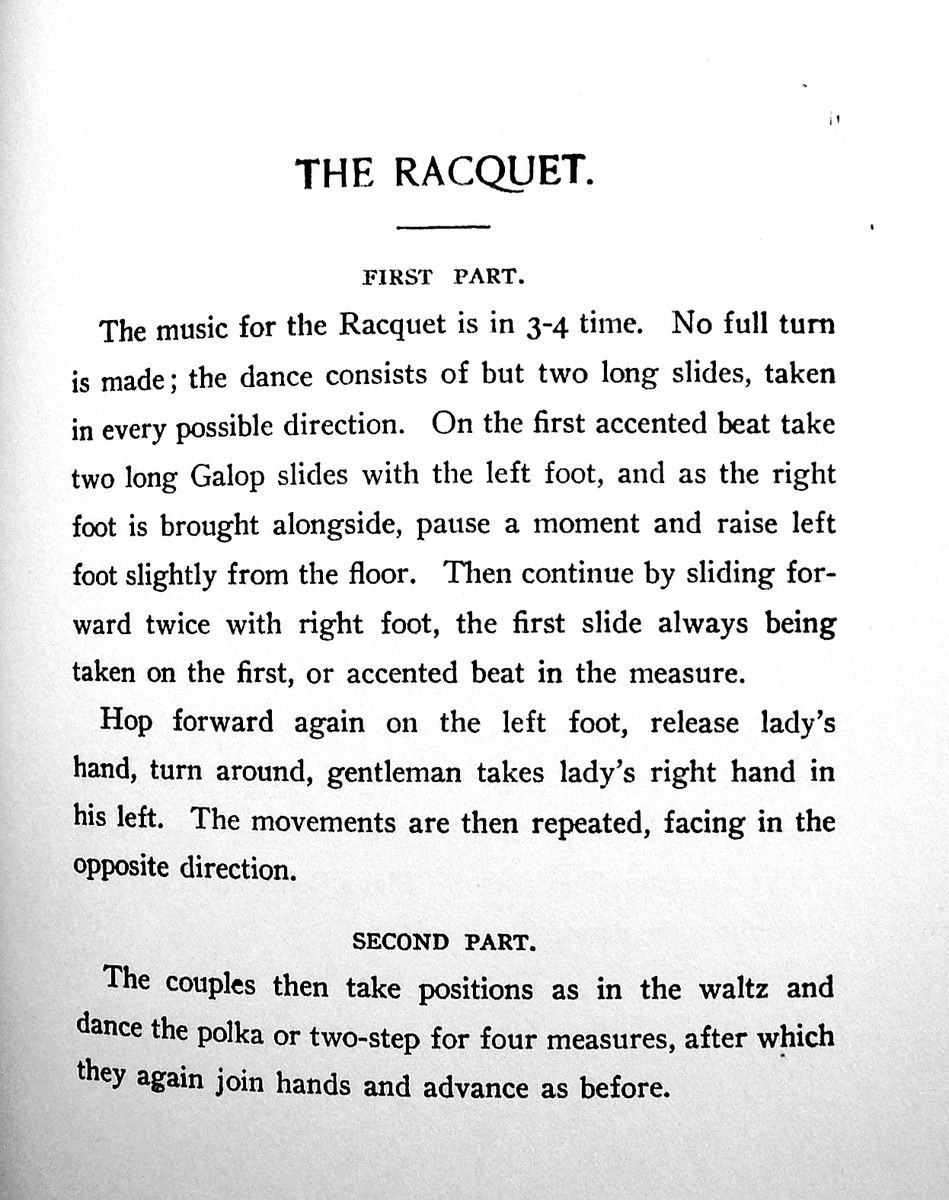

King’s stories of life near Utah’s Great Salt Lake include a wonderful glimpse of rural dancing around 1900:

(more…)